NYT crossword clues, renowned for their wit and complexity, offer a captivating challenge to puzzle enthusiasts worldwide. This guide delves into the art of crafting and deciphering these clues, exploring their stylistic conventions, construction techniques, and the factors contributing to their varying difficulty levels. We’ll examine different clue types, from straightforward definitions to intricate wordplay, and analyze how thematic elements enhance the overall puzzle experience.

Prepare to unlock the secrets behind the seemingly cryptic language of the New York Times crossword!

From understanding the nuances of anagrams and hidden words to recognizing the subtle use of misdirection and puns, this exploration will equip you with the skills to tackle even the most challenging NYT crossword clues. We will also examine the evolution of clue styles over time, highlighting significant trends and stylistic shifts. By the end, you’ll possess a deeper appreciation for the artistry and intellectual stimulation inherent in these iconic puzzles.

Clue Construction Techniques: Nyt Crossword Clues

Crossword clue construction is a delicate art, balancing creativity with precision to create puzzles that are both challenging and rewarding. A well-crafted clue hints at the answer without giving it away, employing a variety of techniques to engage the solver. This section will explore some of the key methods employed in crafting effective and engaging crossword clues.

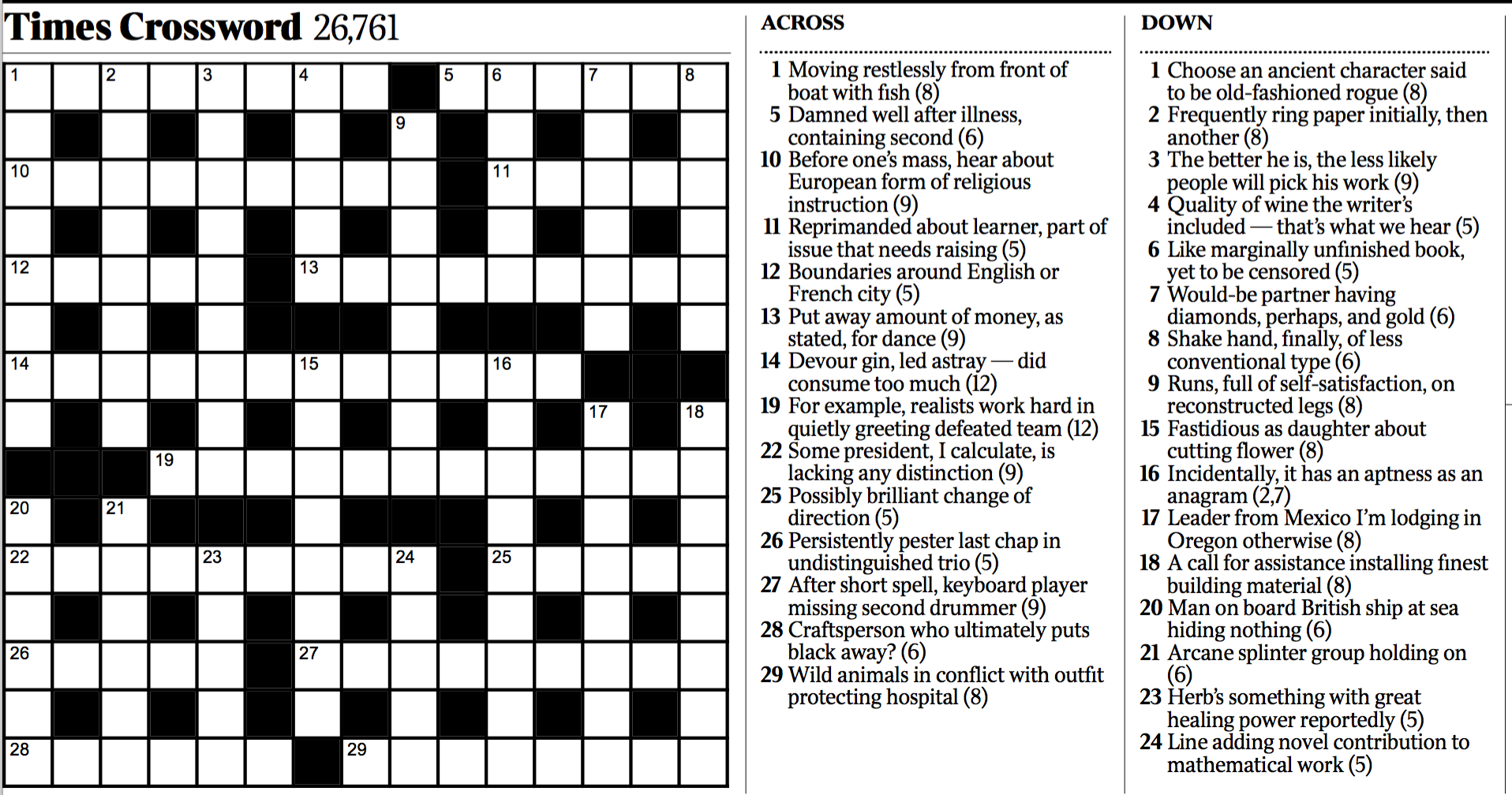

Anagrams, Hidden Words, and Reversals

Anagrams, hidden words, and reversals are common techniques used to add complexity and ingenuity to crossword clues. Anagrams rearrange the letters of a word or phrase to create a new word or phrase. For example, the clue “Upset, as a dog might be (anagram)” could lead to the answer “MAD DOG”. Hidden words involve finding a word concealed within a larger word or phrase.

The clue “Part of a tree (hidden in ‘maple syrup’)”) would yield “PLE”. Reversals use a word spelled backward. The clue “Backward Roman god” would result in the answer “DUS” (a reversal of “SUD”). These techniques require solvers to think laterally and creatively, enhancing the puzzle-solving experience.

The Role of Abbreviations, Slang, and Proper Nouns

Abbreviations, slang, and proper nouns add layers of difficulty and nuance to crossword clues. Abbreviations, such as “St.” for “street” or “RSVP” for “Répondez s’il vous plaît,” require solvers to recognize common shortened forms. Slang, like “hip” for “cool” or “bread” for “money,” introduces a level of informality that can be both challenging and engaging. Proper nouns, referring to specific people, places, or things, often require a degree of general knowledge.

The New York Times crossword puzzles are renowned for their challenging clues and clever wordplay. For those seeking assistance in deciphering these cryptic creations, a valuable resource is readily available: you can find a helpful collection of nyt crossword clues online. These clue collections can provide a boost to your solving skills, allowing you to tackle even the most difficult puzzles with increased confidence.

Whether you’re a seasoned solver or just starting out, exploring these resources can enhance your enjoyment of the NYT crossword experience.

For example, the clue “Author of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird'” clearly points to “LEE”. The skillful use of these elements adds depth and variety to the crossword puzzle.

Synonyms and Related Words

Synonyms and related words are fundamental to clue construction. A simple clue might directly use a synonym, such as “Large (synonym for big)” for “HUGE”. However, more sophisticated clues might use words related by meaning or association. For instance, the clue “Monarch’s residence” could lead to “PALACE”. The subtlety in choosing related words, rather than direct synonyms, makes the clue more challenging and interesting.

This requires the solver to consider the broader context and meaning.

Misleading or Deceptive Phrasing

Misleading or deceptive phrasing is a common technique to elevate the challenge of a crossword clue. This involves using words or phrases that might initially suggest one thing, but ultimately lead to a different answer. For example, a clue like “Sound of a cat” might lead solvers to think of “meow,” but could instead be a cryptic clue for “PURR.” The use of wordplay and unexpected connections creates a sense of surprise and satisfaction when the solver finally unravels the intended meaning.

This deceptive nature adds a significant layer of intellectual stimulation to the puzzle.

The New York Times crossword puzzle is a daily challenge enjoyed by many, and deciphering its clues can be both rewarding and frustrating. Finding helpful resources is key to success, and for those seeking assistance, I recommend checking out this excellent website dedicated to providing solutions and insights: nyt crossword clues. Understanding the nuances of NYT crossword clues can significantly improve your solving skills, leading to a more enjoyable and fulfilling puzzle experience.

Analyzing Clue Difficulty

Creating effective crossword clues requires a nuanced understanding of difficulty. A clue that is too easy is unsatisfying, while one that is too hard can be frustrating. This section explores methods for analyzing and assessing the difficulty of New York Times crossword clues, enabling constructors to better tailor their puzzles to a target audience.

Understanding clue difficulty involves considering various factors that interact to create the overall challenge. A simple-sounding clue might prove surprisingly difficult due to unexpected wordplay, while a seemingly complex clue could be readily solvable with the right knowledge. A systematic approach to analyzing these factors is crucial for consistent clue writing.

Clue Difficulty Comparison

| Clue Text | Answer | Difficulty Level | Explanation of Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opposite of wrong | RIGHT | Easy | This is a straightforward antonym clue, requiring minimal wordplay or specialized knowledge. |

| One might be found in a dog park | POOP | Medium | While the answer is common, the indirect phrasing adds a layer of complexity. Solvers need to infer the connection. |

| Like a well-oiled machine, or a cryptic clue? | SMOOTH | Hard | This clue employs a double definition, referencing both a literal and figurative meaning of “smooth,” along with a meta-reference to cryptic crossword clues. |

| He’s got a lot of nerve | AUDACITY | Medium-Hard | This clue uses idiomatic language, requiring solvers to understand the phrase “a lot of nerve” and its connection to “audacity.” |

Factors Contributing to Clue Difficulty

Several factors contribute to the perceived difficulty of a crossword clue. Careful consideration of these factors allows constructors to fine-tune the challenge presented to solvers.

- Wordplay Complexity: Clues involving puns, anagrams, hidden words, or other wordplay techniques generally increase difficulty. The more layers of wordplay, the harder the clue.

- Obscurity of References: Clues referencing obscure historical figures, literary works, or specialized vocabulary significantly raise the difficulty level. Common knowledge is assumed, but esoteric knowledge is a challenge.

- Misdirection: Clues that intentionally lead solvers down the wrong path by using misleading phrasing or synonyms add a significant layer of difficulty. The more deceptive the misdirection, the more challenging the clue.

- Length of the Answer: Longer answers often require more letters to be filled in from crossings, potentially increasing the difficulty. Shorter answers may be easier to guess based on crossings.

- Commonness of the Answer: Less common words or phrases naturally make a clue more difficult. Frequency of usage in everyday language plays a role.

Patterns Indicating Clue Difficulty, Nyt crossword clues

Certain patterns in clue construction tend to correlate with higher or lower difficulty levels. Recognizing these patterns helps in evaluating and refining clues.

- Simple Definitions: Direct definitions, using common synonyms, usually indicate easier clues.

- Multiple Wordplay Techniques: Clues using several wordplay methods (e.g., anagram and hidden word) are generally harder.

- Cryptic or Indirect Phrasing: Clues that require inference or deduction rather than direct association are often more difficult.

- Specialized Vocabulary or References: Clues employing niche vocabulary or allusions point to a higher difficulty level.

Rubric for Assessing Clue Difficulty

A rubric provides a structured approach to evaluating clue difficulty. This rubric considers several key aspects to provide a comprehensive assessment.

| Criterion | Easy | Medium | Hard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wordplay | None or simple synonym | One type of wordplay (e.g., pun) | Multiple types of wordplay, complex wordplay |

| Vocabulary | Common words | Moderately common words | Uncommon words, specialized vocabulary |

| Referencing | Common knowledge | Some specialized knowledge | Obscure references, specialized knowledge |

| Misdirection | Minimal or none | Slight misdirection | Significant misdirection |

Evolution of NYT Crossword Clues

The New York Times crossword puzzle, a daily ritual for millions, has seen its clues evolve significantly over its long history. Early clues tended towards straightforward definitions, reflecting a simpler approach to wordplay and puzzle construction. However, as the puzzle’s popularity grew and solvers became more sophisticated, so too did the complexity and creativity of the clues. This evolution reflects not only changes in language and culture but also a deliberate effort by constructors to continually challenge and engage their audience.The style and difficulty of NYT crossword clues have undergone a dramatic transformation.

Initially, clues were predominantly straightforward definitions of the answer words. For example, a clue for “DOG” might simply have been “Canine.” Over time, constructors began incorporating more wordplay, puns, and cryptic elements, leading to clues that required more lateral thinking and knowledge of language nuances. This shift was gradual but noticeable, with the introduction of more complex clue structures and a wider range of wordplay techniques.

Clue Construction Techniques Over Time

Early NYT crosswords favored simple, direct definitions. This approach prioritized accessibility and allowed solvers to focus on the mechanics of filling the grid. Later, however, constructors started incorporating more sophisticated techniques, such as cryptic clues, puns, and misdirection. Cryptic clues, for instance, often contain multiple layers of meaning, requiring solvers to decipher wordplay embedded within the clue’s wording.

A clue might use anagrams, hidden words, or double meanings to conceal the answer. The increased use of these techniques has significantly elevated the challenge and intellectual stimulation provided by the puzzle. Consider the difference between a clue like “Man’s best friend” (a straightforward definition for “DOG”) and a clue like “Hound’s home, perhaps?” (a more cryptic clue that plays on the homophone “house”).

Shift in Difficulty Levels and Target Audience

The average difficulty of the NYT crossword has generally increased over time. While the puzzle has always aimed to challenge solvers, the introduction of more complex clue structures and cryptic elements has led to a steeper learning curve for newer solvers. This reflects a changing target audience, as the puzzle has become increasingly popular among experienced solvers who appreciate the intellectual challenge of sophisticated wordplay.

However, constructors also strive to maintain a balance, ensuring that the puzzle remains accessible to a wide range of skill levels. This is often achieved by incorporating a mix of straightforward and more challenging clues within a single puzzle.

Examples of Clues from Different Eras

Comparing clues from different eras vividly illustrates the evolution of the puzzle’s style. A clue from the early 20th century might read: “Large feline.” This simple definition for “LION” stands in stark contrast to a contemporary clue such as “King’s mane, maybe,” which utilizes a metaphorical reference and introduces a level of ambiguity to engage the solver. Similarly, the shift from straightforward synonyms to clues employing puns and wordplay highlights the growing emphasis on creative clue writing.

For example, a simple clue for “RAIN” might be “Precipitation,” while a more modern clue might be “What a downpour might do.” This modern clue utilizes a metaphorical sense of “downpour” to hint at the answer.

Mastering the art of solving NYT crossword clues requires a blend of linguistic skill, logical reasoning, and a healthy dose of perseverance. This guide has provided a framework for understanding the various techniques employed in clue construction, from straightforward definitions to elaborate wordplay. By analyzing clue structure, recognizing patterns, and appreciating the historical evolution of the puzzle, solvers can enhance their skills and unlock the satisfaction of successfully completing even the most challenging NYT crosswords.

The journey into the world of NYT crossword clues is an ongoing adventure, filled with intellectual stimulation and the rewarding feeling of accomplishment.

Question & Answer Hub

What is the average difficulty of a NYT crossword?

The NYT crossword’s difficulty varies daily, but generally ranges from medium to challenging, with some puzzles being significantly harder than others.

Where can I find past NYT crossword puzzles?

Past NYT crossword puzzles can often be found online through various archives and puzzle websites.

Are there any resources available to help improve my NYT crossword skills?

Many online resources, including books and websites, offer tips, strategies, and explanations to improve your crossword solving skills.

What is the difference between a cryptic clue and a straightforward clue?

A straightforward clue directly defines the answer, while a cryptic clue uses wordplay, puns, or misdirection to arrive at the solution.